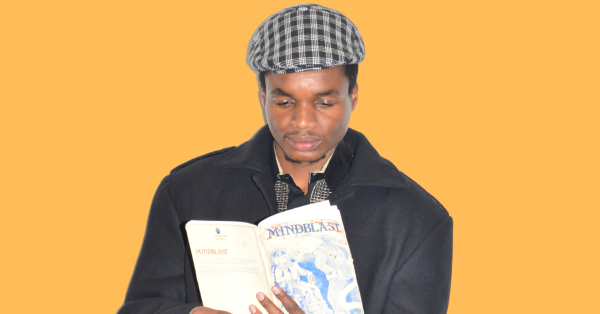

Onai Mushava’s latest definitive collection of poetic offerings has once again raised interest on the intellectual commitment of the poet, his role in capturing the momentous technological breakthroughs of the 21st century and the almost precarious attempt to resuscitate the dying ambers of the power and interest in literature.

Mushava has so far added to Zimbabwe’s literature corpus Rhyme and Resistance, Electronic Ladyland (lockdown poems), and Survivor’s Café.

At the same time, he is currently in the process of chiseling out a singularity-themed body of work whose plot is a futuristic world of revolutionary technology raptured in a dystopia of its own.

While I personally do subscribe to the notion that a poet should be accepting accolades for his creative products that derive from a difficult place of creative impulse and mental suffering, Mushava’s world is not that outrageously complex.

Indeed, his works retain an infinite, almost journalistic love for music, his surprising adoration for the mystically divine, and an appreciation of history even as he seeks to escape from his tormenting available reality into some fantastic place and time.

In an age where the interest in literature is fast wanning as the new generation finds affinity in smartphone technology and motion picture, Mushava seems to find himself marooned at the very edge of the golden era of post-modernist poets.

He writes out of frustration, obduracy and, futilely so, for a generation that no-longer reads as much as the previous one, and an “industry”, as he calls it, crumbling in its own rotten peeling paint of dereliction and corporate apathy.

Yet in successive outbursts of imaginative power, Mushava’s Rhyme and Resistance catches his generation at the meeting point of technology and the bare strips of human condition, converting all this into convoluted masterpieces of written work.

But can he be properly recognized and accepted by a media sunk in the polarity of fractious politics and tabloid scandal, as well as a polity that has a historic weird relationship with rebel art?

It is here where I feel we are on the verge of loss, for in this poet, a new generational movement is emerging to define this present century and iconize it in art and literature, in protest and romance.

Yet he deals with the same conflicting realities of his divisive political cosmos, and thus fails to escape from the collective anger towards the establishment, the gnawing isolation that inspires his creative urge.

That terrible isolation morphs into disillusionment, a total lack of trust in the revolutionary role of the poet in an apathetical, polarized society and thus in Paradzai Mesi of Poetry, he resignedly submits:

…I sing for a cause I no longer understand

The solidarity I cannot feel where I stand…

The poet equally strives to be a generational cogent voice and burgeoning journalist in a country tortured by materialism and online decadence.

Mushava pays homage to the heroic, deified feminine iconology of past figures by experimenting with diction to produce the brutalized condition of his present circumstance and thus: “Nehanda weaned me with poison on her breast”.

The poet is destitute in his own psychedelic cosmos where “Night is my blanket, and the street my headrest,” as well as a forgotten world of poverty, and suffering where “”Homeless sleep is the codeine ocean to deep-dive.”

Apparitions of the Devil are juxtaposed with the President, and as in Platonic Honeymoon, the idea of love breeds conspiracy and mistrust, seeking for the poet’s downfall.

Time and place are not existential concrete constructions, as they drown in phantasmagoria where images can be screenshot from dreams hence Dreamshot.

Mushava is not easy to read, his poetry drowns in powerfully hypnotizing imagery and metaphor, as he seeks to deconstruct the idea of a linear reality.

Take for instance Paper Sunday, an abstractionist experimental poetic form that derives strength from the avant-garde:

…Adam and Eve had Apple shares before Steve Jobs;

Let us rebrand the church with Wall Street paint jobs,

Glossing it green because poverty is so sick like Neyo;

Drugging lice your blood only makes you a parable hero.

Rhyme and Resistance is the uncertain quest and will to establish a line of connection between a creative society and the open fangs of power, and somewhere in the grey area separating the two, he strives for what Dambudzo calls, “A healthy tension between the state and the poet”.

Intentionally or unintentionally, the poet has created an abstract art-piece that exposes a diorama of hell, of disempowerment, rage, lyrical obsession, the unfathomable limits of creative ingenuity and helplessness.

His confrontationist literary approach is aptly captured in Collateral Murder: “Now history is blood under the bridge” and as if echoing the current political mantra of a country being built by its own, Mushava mischievously and seductively plays on this in the lines:

“… Give us a moment to declutter the fridge,

We will rebuild the country brick by brick,

And thatch it with dead protesters’ sticks.”

The writer, in a post-revolution era, is thus tied down to the rolling wheels of a constant war in motion, trapped in a seemingly never-ending restlessness, eccentricity, and a mental affliction of sorts.

In Hystery, the writer is at peace with shouldering the collective hysteria of a disenfranchised millennial generation.

He scuttles into “The president’s toilet” and sees “our chocolate factory” where the poet “is the electric figurine starring his toy story” while the masses are “dreammates in a virtual-reality box, “Picture-perfect playmates of his poverty porn.”

Mushava has reduced his poetry into banners of protest behind which he rallies an iconoclastic voice that is daring and directly provocative yet with a compelling degree of imaginative and intellectual fortitude.

While Dambudzo Marechera strove to be a mega-phone for a lost generation in the dystopia of war and exile, and Mbizo Chirasha struck the impression of a poet at home, Mushava is constantly challenged by the emergent sinister forces of the internet highway, artificial Intelligence, and the arriving train of a technological singularity.

In the alliterative barrage of contrasting diction, Mushava is aware of form and thus arranges his poems into quatrains and tercets laced in delicate rhyme while paneling words into verbally sophisticated scrape.

The complexity of his stream of consciousness is a notably remarkable further development of the Zimbabwean anthology in particular and African literature in general.

Such is the immense quality for a writer who has dabbled into Fyodor’s Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, James Joyce’s modernist Ulysses, and Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis.