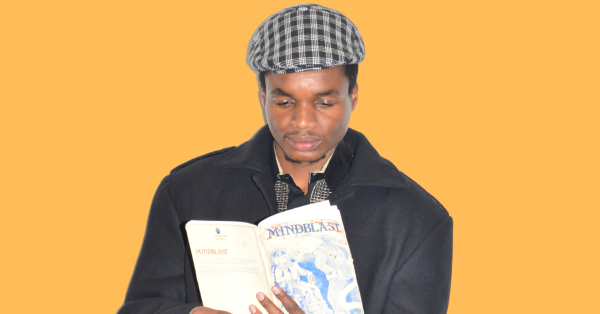

Onai Mushava is a Zimbabwean poet and journalist, noted for his intertextuality and pro-poor themes. In 2018, he won a National Arts Merit Award (NAMA) for Outstanding Fiction Book, becoming one of the category’s youngest winners at 27. He has also been nominated in the poetry and journalism categories.

Mushava’s debut book, Survivors Cafe (2016), combines themes of love, politics and religion, while Rhyme and Resistance (2019) falls within the protest category, as well as exploring the poet’s psyche. In this interview, poet Tafadzwa Chiwanza (TC), whose debut book is due for release next month, interviews Mushava (OM) on the role of religion in his work.

TC: Your early writings were mainly Christian in context, I observed. Why the change?

OM: My first book, Survivor Cafe, is one third gospel; I am really telling you how to go to heaven in those poems. There is more optimism in my early poems; even when I paint apocalyptic pictures, it all ends with Jesus being the answer. The change from sincerity to irony that may be noted in my political poems begins within the religious poems. My Christian poems like “Holy Goldfish” and “Coffee with the Pope” are the first to mark this shift. As time goes on, my faith is not lost at all but I just no longer use religion to shelter myself from the everyday struggle or shy away from the political questions of the day.

TC: So would you say your religious views have been changed or perhaps improved with the journey you have walked so far rather than destroyed as one may be tempted to believe when comparing your earlier works with the recent?

OM: The main change is that I am no longer writing from the pulpit but rather from the confessional. I am as broken as anyone and I am no longer glossing over that with colour poems. A quote like, “I have found Jesus; he lives in my mirror,” from my poem 2019 poem “Holy Joker”, could sound like blasphemy but that’s just me exorcising my narcissism or my Jesus Complex to become a better Christian or just a better person.

My recent poems deal more with cracks in my own personality, my flaws and complexes. I have to reach beneath the colour poems of religion to detect this. I am showing how grand buzzwords about myself distort my relationships with other people, particularly the women in my life, how we drift into mutual alienation while repeating colour phrases. My 2018 poem, “Postcard to Santa”, borders on vulgarity and self-humiliation but that’s just the truth that has to set me free. I still write Christian poems that just don’t immediately look Christian.

Have my views improved? There is the question of justice, which has always been a feature of my poetry, I think. In my early phase, I was a religious moralist and then I was a political prophet. I still have most of the views I had but I just no longer put myself out as a model to be emulated but I exorcise myself in public so that I can prepare myself, maybe others too, for the fight.

TC: Well said. I see the struggle with self seems to have become graver later on in your writing path. You appear to have struggled to strike a balance between the politics of the state, the politics of self, which is now recurring more in your recent works and the blind devotion of a believer.

OM: The spiritual is political. The system sustains itself through spiritual violence – I am looking at deeply held patriarchal entitlements, narcissistic defence mechanisms that thrive in alienation, the blending of the self with the spectacle, the consumer Trojans of protest culture and so on. Before Neo can confront the Matrix, his comrades must pull a family of mind viruses out of him. Confronting the self is the first stage of confronting the system.

In my poetry, the political phase begins with my experience of economic injustice. Last month, I celebrated my first anniversary of unemployment and everything that came before that was underemployment. I guess some millennials can relate with this experience. In one scenario, work takes over your life and alienates you from family, church and other coping mechanisms but you are also not rewarded for it; as far as your bosses are concerned, you are supposed to be grateful you aren’t on the streets. In another scenario, you are down and alert to how everything, including friendship and loyalty, is commercially coordinated.

This was draining my spirit, my pride, everything. I was also unconsciously reorganising my artistic influences. From listening to gospel music only, I was listening to a ton of sungura, reggae and Zimdancehall for economic kinship. Outside these genres, Bob Dylan and Kendrick Lamar became two of my major influences, not just their justice themes but even my return to rhyme and the amount cultural information that spills into my work beginning in 2017. My personae become the presidents, the trolls and so on who boast in the truth at their own expense.

However, the struggle is changing me at the same time; I am taking the mud and I am growing cold; I must necessarily face the politics of the self. Kendrick Lamar seems to do this well. To Pimp a Butterfly both confronts the system and explores the artist’s own psyche, and DAMN. grows on the introspective branch of To Pimp a Butterfly. As far as my own shifts from spirit, state and self, I am anxious not to split my evolution into clean phases. There is cross-contamination at every stage; perhaps I will still go back where I started.

TC: Confronting the self is the first stage of confronting the system. Can a writer remain serine as a dove in his religious works and still be the vengeful eagle in his political works? Is it possible for a writer to maintain his religious sanity while writing from a standpoint of political and economic turmoil?

OM: It seems the usual experience is that one switches from one end to the other, a conversion that mellows the writer down or a loss of faith that is often seen as a loss of naivety, or sometimes seen as a leap into chaos and confrontation. I have written serene Christian poems and vengeful political poems but these belong to different, if cross-contaminated, phases so it’s difficult for me to answer. You risk complacency being serene in these times but then the poet is also privileged with creating alternative reality so that’s something I am not ruling out.

TC: To what extent does the politicisation of religion affect your religious views and devotions?

OM: I find that interesting. From the beginning, my Christian poetry is a rejection of the institutional compromises of mainstream Christianity. In this I am in debt to reformers and even Christian fundamentalists whose bad politics I also detect and discard in time. I risk a lot of abstraction here, but let me say my Pan-Africanism, my Marxism and now my budding feminism has put me into conflict with my colonially entitled white evangelical teachers and my consumerist and complacent black Pentecostal teachers. My ideal Christian is a politically emancipated individual.

TC: Philosophical works of Jean Jacques Rousseau and Thomas Hobbes suggest that there is a strong relation between politics and the religion. As your political views changed, did this also alter your religious devotions?

OM: That’s quite an insight. The assumption also becomes that when you rebel against the politics you also rebel against the religion as these are tied at the backend. This is the basis for the targeting of the state religions of France and Russia in the respective revolutions. This may also be the basis for the Sunken Place reputation Christianity gets among Afrocentric thinkers. But when you look at an atheist philosopher like Slavoj Žižek theorising a materialist Christianity, look at an atheist critic of established religions like Sam Harris exploring the idea of spirituality without religion, or look at a decolonial critic of Christianity like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o weaving justice motifs out of Bible stories, it becomes apparent that there is still so much to redeem from religion for the secular thinker. How much more for the religious thinker?

I find it very easy to differ with any Christian institution or leader as well as religiously promoted consumerism, racial complexes, patriarchy, child abuse and so on. However, I must confess I am very much a Christian apologist when it comes to the Bible and God. I am about an emancipatory reading of the Bible. Reggae has done that but even outside its Rastafarian turn, some of the foremost political musicians – I am thinking of Leonard Zhakata, Bob Dylan and Kendrick Lamar, who are all my favourite artists – are Christians who weaponise the Bible for social justice. That’s where I am at in my evolution.

TC: On a concluding note, can we turn to one of your favourite artists, Kendrick Lamar. Kendrick talks about religion and politics a lot in most of his songs, the Hail Mary verse in “XXX.”, for example. I also notice that in some of your poems such as “Coffee with the Pope”. How does combining these two elements help to bring across the intended message?

OM: Religion in my work is less complicated than it is in Lamar. What you get from Lamar is not simply preaching or celebration but the desperation of “Alright” or the rootlessness of “YAH.” and “FEAR.”, the deferring to God over having no place in the world. This would have had the sound of an alienated sigh for Karl Marx but it’s very much an African-American tradition that probably also explains the rise of consumerist vocabulary in protest music including Lamar’s own, Childish Gambino and, more obviously, the late Pop Smoke. We are looking at the reaching out for a being that you have been denied; a turning to God or consumer goods to find the meaning, the humanity or the validation emptied out of you or withheld from you by the system. For Kendrick, God also seems to be a standard of authenticity in a corporate entanglement that can may be described as selling your soul. The latest Kanye saga, for example, is anticipated in Kendrick’s “God Is Gangsta.”

In common with Kendrick, I have tried to move towards the black joy of Chance the Rapper but in fact relapsed into my darkest poems in the process. Religion gives a singular vocabulary to the pain of failing to belong.

TC: Thank you for the interview, Onai. We must get in touch again and explore a lot more stuff that could only be hinted at in this interview.

OM: Blessings, bro!