When a music career underwhelms, artists are known to lean into religion, exile, retirement, isolation or drugs to wash away the torment. Biggie Tembo picked every life-affirming choice on the table and retooled for an artistic comeback but depression, partly traceable to the back-to-back failure of his two solo albums, cruelly ended his legendary career.

While mental health issues in the arts are becoming more openly talked about – not without stigma, even in 2018 – in the 1990s’ Zimbabwe, depression was not topical. The greatest Zimbabwean to ever hold a microphone sought calm for his dark days in music but lack of support tossed him over to the bottle, the ancestors, the church and, tragically, suicide.

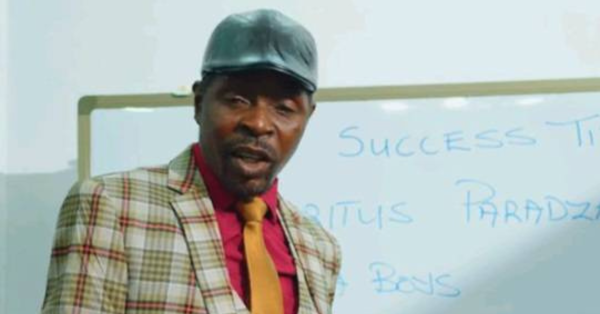

I had the privilege of listening to Biggie’s last two albums, Out of Africa and Baba of Jit hoping to pick scattered hints of what the former Bhundu Boys frontman might have been going through. Both albums were recorded with the backing of Ocean City Band – the group famously fronted by Safirio Madzikatire and, later, James Chimombe – at Steve Roskilly’s Shed Studios.

For an icon Biggie’s size, it is sad that both albums, like most of The Bhundu Boys’ discography, are now lost – neither circulated nor curated in Zimbabwe. Perhaps, this neglect of a national treasure is only thing that would have topped the ungenerous reception that drove him into depression.

“The lack of success with this album and the lack of being still part of The Bhundu Boys has just driven me to such despair that something flipped in my brain and I wasn’t in control of myself anymore,” Biggie told Roskilly towards his last days, as the latter recalls in the Elton Mjanana-directed Absolute Jit documentary.

Out of Africa is the more solid artwork, spawning memorable hits like the poetically cryptic “Punza” and the politically assertive “Mozampique.”Baba of Jit is, on the other hand, filled with themes of loss, subdued, resigned, sorrowfully see-through, nostalgic for career highlights without quite recapturing them, content with literalist songwriting and reflective of his born-again Christian experience.

“Rufu,” the Oliver Mtukudzi-assisted tribute to Bhundu Boys bassist David Mankaba – who succumbed to an AIDS-related illness, aged only 33, having become the first Zimbabwean celebrity to openly say that he was suffering from the condition –is the probably the closest fans can remember from the album.

The chemistry is more obvious than what you get on recent Tuku collaboration where the superstar just superimposes his voice on someone’s song without being convincingly part of it. Biggie and Tuku were to feature in another Mankaba tribute, “Chenjerera Upenyu,” before AIDS further depleted the band, claiming Shakespeare Kangwena and Shepherd Munyama.

Even the love songs (“Rudo” and “Zvingaome”) lack the famous Biggie Tembo telepathy and the Ocean City backing does not quite match the Bhundu energy. Biggie leans more to sorrow than the dance music for which he was renowned. The compositions play around the dark material of divorce, cuckoldry and death.

When he wears his pastoral collar (he hung himself two months away from completing a pastoral diploma with Zaoga and Leonard Zhakata says he took him to the church he subsequently attended for twenty years) there is more of surrender than cheerfulness.

The compositions lack the varied personae, storytelling and humour of earlier albums, even though the outlook on life sounds more mature. He is not struggling against life on his own terms but accepting it and philosophising it in a way that sounds less artistic. On music-about-music songs (“Maungira” and “Mbiri Yechitsiga”), the jit vibe is loudly absent. Still, I find the sincerity and vulnerability Biggie brings to this record priceless.

The stronger artistic is to be found on “Out of Africa” with even on the lesser known jams like “Mushonga,” “Harare Jit,” “Ngaraire,” “Out of Africa,” “Jinga” and “Nherera.” It is the beautiful record that did not get a fair chance at shelf life.

Roskilly recalls the “Simbimbino” singer packing everything into the album for a comeback. “He had a big launch party at a hotel and played bits of this live and bits of this from the album, and invited all the journalists, all the music press, just did a proper launch as it should be done.” Roskilly recalls. “But the production value just wasn’t there and it didn’t make anything again.”

His subsequent collaboration with British band Startled Insects underwhelmed while a surprise venture into stand-up comedy was laughable but not in the complimentary way. The next time Roskilly heard of him, was in a psychiatric ward in Chinhoyi hospital, having been given similar attention in a British hospital before deportation.

BBC’s Andy Kershaw remembers The Bhundu Boys as the single most natural, effortless and catchy pop band. “I went to Zimbabwe at the height of it and saw all the groups, and although I championed people like the Four Brothers and John Chibadura, it was blindingly obvious what the Bhundu Boys had over them all: they had great tunes, musicianship and a pop sensibility; they had the personality…

“In terms of personality, their big asset was Biggie. He was a great character on stage, a great communicator. The biggest mistake they ever made was to get rid of him. He was the front man, the spokesman, the leader and the ambassador. Everyone loved him, and he loved that role,” Kershaw recalls the Zimbabwean great.

Let us talk about securing shelf space for legacy creations of Zimbabwean art. Biggie is a matchless genius and a national treasure. Who is looking out for him?