|

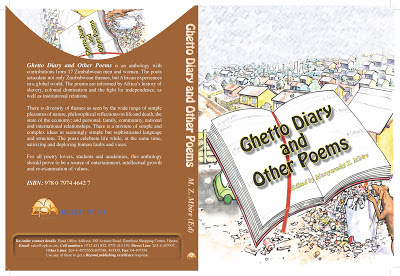

| Ghetto Diary and Other Poems |

Book: Ghetto Diary and Other Poems

Editor: Munyaradzi Z. Mbire

Publisher: ZPH Publishers (2011)

Zimbabwean poetry is a cosmopolitan office. Few local poets seek to make a conventional impression, hence the counterpoint of angles which inheres in the tradition.

The tradition is a melting pot where individual perceptions, native sensibilities, contra-conventional attitudes, universal experiences and aesthetic devices simmer to generate flavours adapted to varied tastes.

Flora Veit-Wild observes that despite sharing a setting where experiences such as the search for identity, effects of urbanisation and colonial devastations often line the task-pane, they are notable differences in how Zimbabwean poets respond to common experiences.

“Depending on their age, their individual backgrounds and their education, they show very different preoccupations, approaches and styles,” Veit-Wild notes in “Patterns of Poetry in Zimbabwe,” with particular reference to the so-called lost generation of Zimbabwean literature.

The contemporary poets maintain this detachment from set templates but seem to share one thing above all, namely the tradition of questioning, in the way they grapple with challenges obtaining in their broader environs.

Since Pathisa Nyathi portrayed as the poet as a statesman in an artistic mantle in “Till the Silence be Broken,” several poets have utilised their poetic licence to deliberate state affairs in their immediate and remote dynamics.

There has been a representative volume for each epoch; “Zimbabwe Poetry in English” (anachronistically, in this case) to capture the founding era of nationalism and rediscovery, “And Now the Poets Speak” to reflect on the liberation struggle and post-colonial anticipation and “State of the Nation” to appraise the turbulent years.

“Ghetto Diary and Other Poems,” one of the more recent collections, is not a response to a particular period but crosses varied spectra, engaging matters of universal concern such as life and death, love, family, community, family, morality and geopolitics.

The featured poets, however, retain a nationalist command as they relate Zimbabwean and African experiences, recapturing the continent’s progress through slavery, colonialism, liberation, neo-colonial subjugation, skewed multi-lateral relationships and the trending aspects of globalisation.

The anthology is poorer for lack of a prefatory section, thematic segments and biographical information on the contributors, which might have otherwise enhanced reader insight.

On the positive side, however, the arrangement gives each poet ample space to establish unity of thought and exhibit their individual niche in a holistic sequence without losing track by being fitted in a generic school.

Clarity and minute perceptiveness come across as recurrent attributes in much of the anthology. The poets have remarkably severed their wares from the sophistication of most of the early poets whose work intimidated readers with its heavy diction.

The title piece “Ghetto Diary” by Ethel Kabwato serialises typical scenes of high density life. Ghetto images like cooking smoke occasioned by incessant power cuts, early morning gossip over the fence, headaches over soccer results, probably as bets prove badly calculated, small house fracases, high water bills when there is no running water for the greater part of the month and demolition of tuckshops are strung together in the poem.

The opening contribution is from David Mungoshi an award-winning novelist who had a colourful stint as Moto’s literary columnist using the pseudonym Chigango Musandireve during the 90’s.

Mungoshi takes on the materialist tendencies in today’s religion in the poem “Seen on a blotter in a bank.” The persona prays to God to guarantee his business interests, meticulously quoting scriptures to move the heart of God before exclaiming “Cheers Good Lord/ See you in the chapel.”

One encounters an inventory of priorities where worship is second fiddle to monetary pursuits and prayer is manipulated into a means to an end rather than interaction with God.

In “Friend Peasant Farmer,” Mungoshi pays homage to that forgotten mainstay of the nation and challenges society’s demeaning evaluation of the rural population. The poem recounts the exploits of peasants in the service of the nation, mobilising support for the comrades, being tortured by foreign soldiers and providing the majority votes.

Mungoshi announces at length “Now a new struggle has started/ And must needs intensify/ Lest hunger stalk us perpetually.” One is reminded of William Wordsworth’s “Resolution and Independence” where a poor and old man determined to eke out an honest living by utilising the means at his disposal instead of waiting for intervention affects a change in Wordsworth.

“Ghetto Diary and Other Poems” is a departure-point from some of the recent anthologies where focus almost exclusively on the single narrative of political crisis. There are poems which do not consign the deliberation of vice and virtue to broadsheet political players but extends it to everyday characters.

If anything, it demonstrates that the malfeasances of those who make it to the public pedestal are not their inventions but products of the society from which they emerge.

Theodora Chirapa is the anthology’s ultimate social evangelist with her chronicles of the multi-pronged ills visited on society by promiscuity and infidelity. “Abortion’s Backstreet” is an S.O.S for babies made and sacrificed in the illicit rites of sex outside marriage. One is compelled to agree with the pro-life rationale that abortion cannot be made safe because it always ends in someone dying.

“Love Child,” “The Vulture,” “The Wolf,” “Liberian Lover,” and “Lollipop Man” decry a host of sexual indiscretions including teacher-student affairs, small (some call them smell) houses, paedophilia and relationships entered on convenience rather than affection with émigrés.

Taking the discussion further from Zvisinei Sandi’s poems which border on sensuality in its immediate appeal not its aftermath, Chirapa presents the social horrors of intimacy outside matrimonial circles and invokes divine justice: “Judgement day is coming/ And the bleating lamps/ refuse to be silenced any longer.”

Eresina Hwede’s poetry is conversational and engaging notwithstanding its apparent technical baldness. “Men of Africa I blame you” rues the conflicts which have riven the region, including in Sudan, DRC and Somalia.

She asks simple, seldom asked questions like “What would you be thinking when you go out to buy guns to kill your own?” – a pertinent question considering that Africa’s trouble spots are perpetually impoverished despite having strategic resources because negative energy is expended on conflict instead of development.

In “Of buying and selling,” Magosvongwe laments the essential obsolescence of marriage and asks the disturbing question: “are we not selling merely our sisters joyfully/ to other men/ and/ buying our wives for our mothers/ with the help of our aunts and our sisters?”

As family goes dysfunctional, assailed by modernist broadsides, the question becomes expedient even in the our ostensibly conservative society where some spouses are just fellow tenants, shut away from each other by professional, technological, egoistic and extra-marital middle walls.

Veteran writer, journalist and ex-combatant Alexander Kanengoni relives hair-raising accounts of the liberation struggle. “Nyadzonia Massacre” and “One Day at Doerei Refugee Camp” recall the vulnerability and anxiety associated with the struggle, unsettling the reader with such lines as “We have had/ A sumptuous meal/ Of fried anxiety/ What now remains is just waiting.” Other poems recall lost opportunities, idyllic and melancholic like the later Thomas Hardy.

Zimbabwean poetry is in its twilight stretch, with most publishers rejecting poetry anthologies because of the limited market. Hopefully, “Ghetto Diary and Other Poems” will give a good account of the tradition.