|

| Mabasa’s award-winning novel |

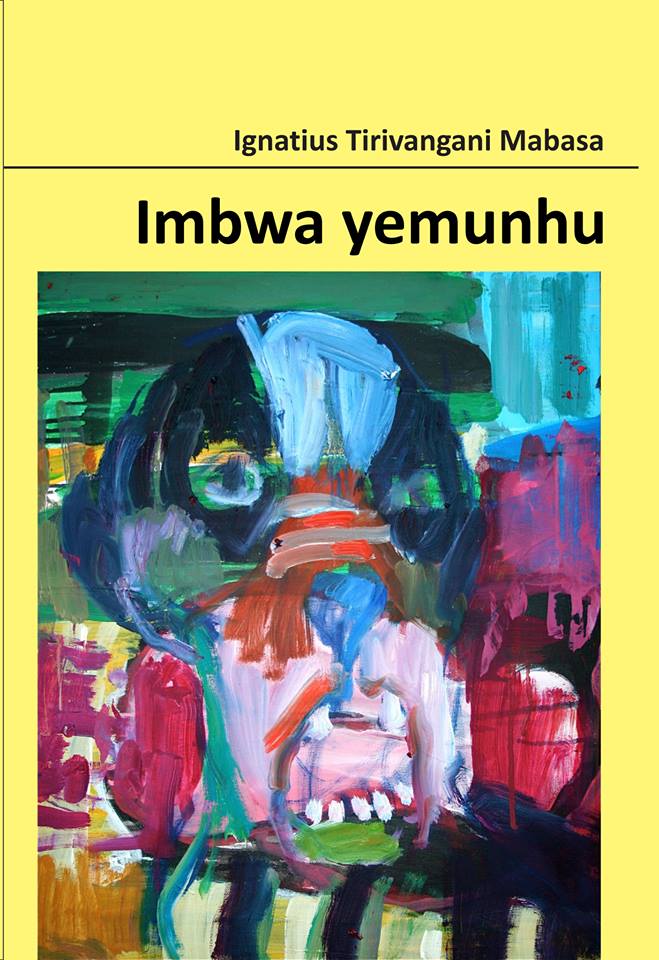

Book: Imbwa Yemunhu

Author: Ignatius Mabasa

Publisher: Bhabhu Books (2013)

Ignatius T. Mabasa’s new novel “Imbwa Yemunhu” is an unsettling anatomy of the human condition. Mabasa fashions his protagonist into a laboratory dummy whom he dissects with a range of technical scalpels to demonstrate mankind’s struggle with the futility of life, diversion and the ultimate quest for spiritual fulfillment.

“Imbwa Yemunhu” is Mabasa’s third novel following “Mapenzi” and “Ndafa Here?” and the first signature offering from his newly established publishing house Bhabhu Books. The stable, which is consecrated to promoting the Shona language, already boasts a gangly alliance featuring Memory Chirere, Tinashe Muchuri, Clever Kavenga and Jerry Zondo.

The novel is a dumpsite of experimental devices including the characterisation of the late dendera maestro Simon Chimbetu as a preacher in the afterlife. Recurrent allusion to yesteryear artists such as Safirio Madzikatire, Biggie Tembo, James Chimombe, John Chibadura and Dambudzo Marechera gives the book an old school, nostalgic feel and intertextual edge.

Mabasa reverts to the stream of consciousness medium, which has been forcefully exploited in a fistful of local masterpieces, chiefly “Kunyarara Hakusi Kutatura” and “Bones” to capture the story of Musavhaya, an obscure writer who defies convention and evades family efforts for him to settle down.

The tragicomic protagonist, whose life and language are replete with dog imagery, is an epitome of purposelessness. Mabasa has been obsessed with dogs lately, the same way T.S Eliot was obsessed with cats to the point of dedicating a whole anthology to Macavity and company. No wonder the nutty novelist’s column in “Kwayedza” is taglined “Imbwa Haihukuri Sadza,” loosely translated “A Dog Doesn’t Bark at Sadza.”

The title “Imbwa Yemunhu” (Dog-Man) refers to the dog-like aversion to restraint to which Musavhaya, an alcoholic and love rat who lives just for the moment, is captive. He lends himself to revelry and lasciviousness to plug the gnawing spiritual void in him. Unfortunately, his problems only disentangle from him at the entrance of the bar, only to confront more relentlessly as soon as the temporary stupor clears.

The novelist presents readers with an amplified prototype of the modern man – one that is haunted by spiritual bankruptcy and consolidates rather than forfeits his problems by escaping instead of confronting them.

Musa is hostage to a spiritual crisis which threatens to implode him. This debilitating conflict becomes a framing point for Mabasa to usher the reader into the realities of both worlds. Through the mind of a character who tries to embolden himself for what he knows is right but melts into passivity the moment he comes face to face with carnal enticements, readers get a view of their own spiritual struggles.

Liberal allusiveness becomes a window for Mabasa to recycle problems raised by earlier artists for fresh deliberation. For a tradition that is on shifting ground, having ceded its founding vitality and visibility to emergent phenomena, Mabasa injects Shona fiction with a fresh stimulus by balancing experiment with example.

The device, which Mabasa extends to the works of his predecessors, including Aaron Chiundura Moyo and Solomon Mutswairo, is actually the mainstay of great world literature. W. B Yeats laments in “Three Movements” that whereas Shakespearean and Romantic fish swam in the sea, modernism is a casualty of its detachment from tradition.

Mabasa’s ability to hunch readers over the narrative from cover to cover is in his mastery of variety. The more accomplished modernist texts such as “The Wasteland” and “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” buttress their claim to immortality by interlacing new trails with classic snippets. Mabasa’s cross-fertilisation of experimentation and popular Zimbabwean art secures him a place among the greats.

“Imbwa Yemunhu” revives the debate on stereotypes in African literature, with a rather dualistic bearing. The wife of a key politician asks Musa “Why are your fellow writers, especially those who write in English, packaging for offshore markets our poverty, our diseases, our wars and such like in return for money, fame and awards?”

Musa decries the fallacy of Africans seeing themselves through the lenses of CNN and BBC but protests against an elitist, lip-service Pan-Africanism whereby politicians eulogise Africa in speeches but short-change it by spending locally earned money in offshore destinations.

The book is divided into random sections with sudden, often eccentric and unpredictable, headers, with the stacks of prose occasionally broken up by poetic interludes from Musa and the Resident Poet of Chikwanha township who claims to be a nephew of Dambudzo Marechera. A light-hearted approach to conversation with recurrent code-switching makes the narrative more real and accessible, capturing serious issues from the medium of colloquial, often humorous, communication.

“Imbwa Yemunhu,” from Mabasa’s own estimate, is a narrative which flows like water, is sweet like honey and bites like a dog; a narrative replete with madness, prostitution, hunger for life, love, fear, drunkenness, hell and every condition to burden and scandalise the reader. “The language of this book captures the times we are now living in. The story of this book captures the reality of what is in many people’s lives – we are fighting against many demons in life, we are fighting against our own powerlessness as mankind, and we are forfeiting the opportunities which God gives to us instead of utilising them.”

There is also match-making gone bad. Musa thumps his nose at the woman chosen by his family as a ticket for settling down while his friend Richard marries Juli more for social ornament than a companion. The latter is obsessed with money and “spinning deals” to a point whereby he has neither time nor affection for his spouse. Musa comes into the picture and has an illicit affair with his friend’s wife.

The character of Simon Chimbetu is another ingenious experiment. Chimbetu is shown in heaven, conversing with Musa and an angel. Chimbetu ends up treating the writer to a celestial monologue in which he harps on the futility of everything: “It is futile to be acquainted with the authorities of any place so that you can jump the queue. If you jump the queue, you with still leave your money and your morality to those who carried you over.”

Chopper, who anticipates judgement at Christ’s second coming, tells an angel he has been discussing with John Chibadura how he wishes they had taken the opportunity to exhort people to worship God while they were entertaining them.

The denouement of the novel is the embattled protagonist’s “Over to you, Christ” decision and acceptance of the evangelical commission. If literature had been written off as a casualty of the digital holocaust, Mabasa’s new masterpiece will force a rethink.

“Imbwa Yemumhu” jointly won the NAMA Best Fiction for 2013 accolade with Charles Mungoshi’s “Branching Streams Flow in the Dark.”