|

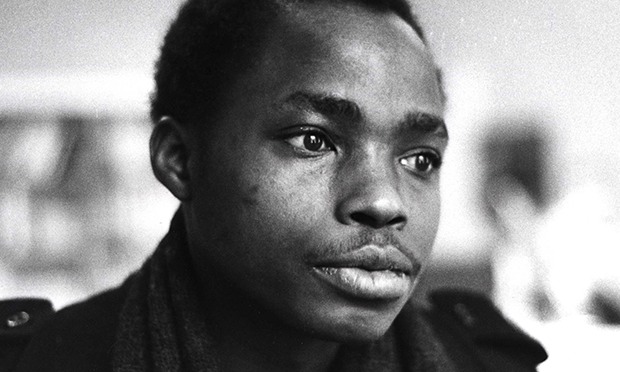

| Dambudzo Marechera (Photo Credit: The Guardian) |

Zimbabwe’s hardcore novelist Dambudzo Marechera is the object of routine post-mortems.

Locating an ideological compartment for the lost generation writer seems twice as impossible as finding a needle in a tonne of haystack.

However, there is something of heroic allure in Marechera’s refusal to be confined in the mediocrity, hypocrisy, subservience and irrationality which often constitute the four wheels of conventional bandwagons.

Notwithstanding the allusiveness which runs the thread of his prose, Marechera’s work is firewalled by a stubborn determination not to cede his intellectual autonomy.

The varied applications on his literary taskbar engage external frames of reference but influence is invoked not so much to submerge as to buttress his output.

The firewall enables a stand-alone artistic universe by and large the emanation of his own existence with its corresponding phenomena, spheres of interaction and field of imagination.

In this Marechera evades the simplistic conservatism and the monotony which plagues several of his less eloquent local predecessors.

The mojo is in his deliberate contravention of normative outlines in preference of his immediate environs and empirical experience as the substance of art.

Not only does he grapple against the anxiety of influence, that seeping contagion diagnosed by Harold Bloom; his avant-garde work ethic cuts him out for a literary progenitor, lynchpin and cult-figure in his own right.

His vastly diverging body of work becomes a launch pad for budding writers bent on hurling their disillusionment, defiance and anger at the world.

Proponents of tradition can only size him up and level a case against his self-confessed cultural sacrileges at the peril of a fanatic backlash, if at all they can summon their eloquence against him.

The last time I faulted Marechera, on good reason, for ethical flaws, I found myself straying into a hornets’ nest, hauled before social media tribunals, flogged for messing up with an infallible genius, indicted for pentecostal bigotry and anathemised for primitive tastes.

All the same, I find still revolting and grossly unwarranted the indiscriminate veneration of Marechera’s work, particularly his individualism, anarchy, obscenity, secularism, post-modernism and defeatism.

Marechera fanaticism also strikes me as ironic in this respect: a generation of faint clones hanging on to his coattails at all costs instead of blazing independent trails as he would have done.

Marechera has also become a template of choice in the post-nationalist framing of Africa. Where the abjuration “I am not an African writer” is invoked, identity and responsibility wax negligible.

Ethically challenged liberals in search of a wall to lean on also find it compelling to conjure up Marechera as a cult figure whom it is impossible to find fault with.

Huge claims from his work are recycled unquestioningly at the expense of rational discourse and to the downgrade of ethical sensibility.

Marechera comes across as a critic without solutions, perceptive in his surveillance of the monstrosities of power and absurdities of blind allegiance but equally wayward as the targets of his derision in his counter-prescription of egocentrism and his sustained attack on morality.

To his credit, Marechera remains one of the most incisive critics of power and at one with the underdog in his short-circuiting of its artificial buttresses.

His “literary shock treatment” stands out as the polar extreme of artists and political players who are at once public crusaders and private sceptics of the same cause.

Stanelake Samkange, a target of satire in Marechera’s “Black Insider,” demonstrates this fallacy: disconnecting from conviction and working from a normative outline which the artist is sceptical about.

“I appear to have come to the conclusion that one of the most important principle – that of love of one’s fellow men and sacrifice and service towards other people is not worth it and is plain rubbish,” Samkange is cited as intimating to Terence Ranger in the latter’s “Writing Revolt.”

On the contrary, Marechera wants to zero in on the urgent, the current and the empirical; to double-underline them instead of airbrushed frames which have no perceptible bearing on the people.

While Marechera is not exactly a “people’s artist” in the sense of writing to champion a collective cause, his disgruntlement with the pretenses of the powerful intersects with unvoiced concerns of Africa’s silent majorities.

“We now do the same thing; we raise the African flag to fly in the face of the wind and cannot see the actually living blacks having their heads smashed open with hammers in Kampala,” the rave chatterbox in “The Black Insider,” apparently a variant of Marechera, observes.

“We have done such a good advertising and public relations stunt with our African image that all horrors committed under its lips merely reinforce admiration for the new clothes we acquired with independence.

“And, of course, the horrors are themselves one more reason to tighten the screws of our peculiar brand of fascism,” he says.

Marechera understood the vast expanse which separates the Africa portrayed in exalted, overused and clichéd prose and the Africa everywhere inundate with atrocities against the defenseless.

There comes the test for our aversion to stereotypes. Exactly what or who are we protecting when we want the unflattering details of our continent – the stubborn realities of corruption, hunger, homelessness, civil war and child soldiers – effaced from the African picture for airbrushed, rose-coloured pixels?

This is one question I have long grappled with and I will maintain that our foremost port of call is fighting poverty and inequality on the ground instead of chlorinating the same from how we present ourselves to the world.

In spite of its absurdities and train of expletives, “Mindblast” is a scathing polemic on the politics of transition. The last play short-circuits the devises of political language under which greed and betrayal flourishes – very much the undoing of the African promise.

Religion is a recurrent theme in Marechera, as in major African literature, more often than not as a punching bag; grossly misinterpreted and misrepresented.

Again, Marechera is articulate with criticism but wayward with his solutions.

Marota’s reprimand of the Bishop in “The Black Insider” demonstrates how the self-directed application of religion by its custodians to the disenfranchisement of the masses has furthered incredulity.

“You carry your God too high above the trees. The people cannot see him. All they see is the smoke and shrapnel of their own kind killed your orders,” Marota tells the Bishop.

The context is the Bishop’s furnishing of theologically contrived justifications of the ill-reputed Zimbabwe-Rhodesia government’s indiscretions, particularly approval for cross-border bombings on refugee camps.

Custodians have dealt religion a major disservice by failing to adapt it to social needs, rather manipulating it into an instrument for the subjugation of the poor and lowly.

This probably explains the mass appeal registered by emergent charismatic preachers who take a holistic approach to Christianity and address concerns for “this life and the life to come.”

Marechera and a host of other African writers – notably Okot P’Bitek, whose persona calls God “hunchback” and pours cold scorn on Christianity – veer off-rail when they confuse hypocrisy for faith and incriminate the latter on behalf of the former.

An expansive current of new writing within the tradition of Afrocentric Pentecostalism – Mensa Otabil’s “Beyond the Rivers of Ethiopia,” Matthew Ashimolowo’s “What’s Wrong with Being Black?”Andrew Wutawunashe’s “Dear Africa: The Call of the African Dream” and

other titles – is a refreshing alternative.

There is need to extend this kind of writing to the creative and scholarly domains to consolidate the emancipation of Africa from psychological fetters and maximise our people’s potential.

My last gripe against the Marechera craze is not so much against his work as a “bad influence” but against his adherents as receptacles without mediating capacity.

One of Pope Marechera’s Swiss Guards, Tinashe Mushakavanhu, who now chairs Dambudzo Marechera Trust references as the downside of Marechera fanaticism the creation of “literary zombies” who speak and write without thinking, read without understanding and look without seeing.